What's behind 17A? for Going Places

Back when it used to be a prominent red-light district in Singapore, Keong Saik Road and its surround have left a lasting impression on author Charmaine Leung’s identity – impactful enough for her to write a book about her memories and experiences of the neighbourhood.

While Keong Saik has lost not only its notorious roots but also a certain sense of community since then, the stories live on in Charmaine’s book 17A Keong Saik Road, revealing a colourful but wistful side of Keong Saik that is beginning to be forgotten.

1. Your book name is also an address. How is this significant?

My mother operated a brothel here when I was growing up from the 70s to the 80s. I will always remember it as a place that ‘separated’ my mother and me. We had to live apart from each other.

Growing up in 15A Keong Saik Road

But, it is also because of this address that I had the chance to meet many amazing and courageous women who influenced my life till this day. Their spirit of resilience and how they persevered to make life work against all odds are a constant inspiration for me.

Charmaine's grandmother and her mother posing in a studio

Today, 17A Keong Saik Road is the address of a restaurant.

Tell us more about your neighbours living in the area.

The people who lived in the neighbourhood were mainly Chinese, though a small population of Indians also lived in Keong Saik. The Chinese community were made up of clan associations and business owners who had their businesses on the ground floor units, brothel operators and ma je who worked in the brothels, ladies (dai gu liongs) who were sex workers, as well as others who needed a roof over their heads after a long day’s work.

I lived at 15A Keong Saik Road with my nanny, and the neighbours who lived directly above our unit at 15B was a family of seven: the father was a lorry driver, his wife a fishmonger, and they had three daughters and two sons. They also made parts of their space into cubicle rooms and leased them out to a seamstress and a cosmetics salesman who worked in Outram Park.

There was a great sense of community and belonging amongst the neighbours – a village-like atmosphere where everyone who worked and lived on those streets was friendly and seemed to know, or know of, one another. We could easily tell who was a gai fong (resident of the street) and who was a visitor to the area.

What was it like growing up in Keong Saik?

Growing up on Keong Saik was colourful. The sense of community in a village-like manner was probably the closest thing I could experience to living in a real kampung.

Little Charmaine posing at 'her playground'

As a kid, I was allowed to run along the covered five-foot walkways on Keong Saik as long as I did not cross what the adults called my ‘boundaries’ – the junctions at Keong Saik and Kreta Ayer Road, Keong Saik and Neil Road, and Teck Lim and Neil Road – where the traffic was heavy with cars. I also got to roam the grass areas at what is known as Duxton Plains Park today. I used to run up and down the green slopes, playing catch with my childhood playmates.

Which building was a major part of your childhood?

The triangular-shaped building. It used to house Tong Ah Coffee Shop. This used to be the place where residents of Keong Saik gathered in the morning for breakfast and their daily dose of gossip. I loved having the butter and kaya toast from Tong Ah for breakfast!

What is one thing that has not changed?

The sheltered ‘five-foot ways’. It is the one thing that has not changed for me in Keong Saik no matter how the inhabitants of the street, residents or business, have evolved over time.

I still feel that same ambience I used to feel walking under these covered walkways today. This is especially around the area near the Chinese temple located at 13 Keong Saik Road where, as a child, I used to look up at the large lanterns hanging above me as I passed them.

What is your one favourite building in the neighbourhood?

It is the building at 15 Keong Saik Road but not because I used to live there! 15 Keong Saik Road has what I would consider the best view of the entire Keong Saik stretch. It is situated at the intersection overlooking the three streets of Keog Saik, Jiak Chuan and Teck Lim Road. It was very good for people-watching. Today, it houses the Singapore office of ARD German Radio and TV.

What is one particular memory of the place that does not exist anymore?

Instead of thinking of a place, a whole community of ma je who was living and working on Keong Saik comes to my mind. They used to be such a common sight in the Keong Saik area and in Chinatown.

Ma Jie celebrating at a gathering

The friendships they had with each other left a deep impression on me – they were always looking out for one another, and coming to the rescue of their ‘sisters’ in need. Today, very few of them are left, and the last of them are probably in their nineties. They are a part of our history that will be forever lost.

What building has been particularly well preserved over the years?

The Chinese temple at 13 Keong Saik Road looks exactly like how I remembered it when I was growing up, and when I revisited the area in early 2000s. Although it did not add any fresh colours of paint like some of the other shophouses in Keong Saik did, it is well preserved over the years and has stood the test of time.

How do you feel about the evolving changes in the neighbourhood?

What I miss is the old neighbourhood with the people who used to live in Keong Saik. Today, it is a very different community, made up mostly of businesses, restaurants and cafes. I don’t think many people live in Keong Saik anymore. In that sense, it will never be the same Keong Saik for me.

However, I am glad to see the conservation efforts in the area. In Singapore, many old buildings have been demolished to make way for new developments. At least, I know I will always be able to point out to visitors where I used to live and play amongst these houses and alleys.

How do you think a balance can be achieved between making space for the new and preserving heritage?

I think preserving heritage does not necessarily have to be a trade-off between the new and the old. Holding onto the past for the sake of preserving heritage may not be realistic. It is also about evolution, and perhaps looking at adaptive reuse, that is, how an old building can be used in today’s context.

Take for example, The Warehouse Hotel at Havelock Road which was awarded the 2017 Architectural Heritage Awards for restoration and innovations. The character of the former warehouse has been retained while innovations were introduced to adapt that building to a new use, making it relevant for the travellers of today.

We also need to continuously educate people on the importance of heritage, and make it interesting for our future generations to want to know, explore, and make their own interpretations of heritage.

What is the lasting legacy of Keong Saik that you want people to remember?

I hope people can remember Keong Saik as a place where our forebears had come to settle from China, worked hard to make a living, and left an imprint here. It was not merely streets that provided entertainment to pleasure seekers, but a place where a community of people, despite their difficulties, persevered in working towards the hope of a better future.

Keong Saik can, and should, serve as an inspiration, or a reminder, of how far Singapore has come as a country made up mainly of immigrants who left their home countries to make a life for themselves.

17A Keong Saik Road recounts Charmaine Leung’s growing-up years on Keong Saik Road in the 1970s when it was a prominent red-light precinct in Chinatown in Singapore. An interweaving of past and present narratives, 17A Keong Saik Road tells of her mother’s journey as a young child put up for sale to becoming the madame of a brothel in Keong Saik. Unfolding her story as the daughter of a brothel operator and witnessing these changes to her family, Charmaine traces the transformation of the Keong Saik area from the 1930s to the present, and through writing, finds reconciliation.

Balinese Sojourn for Design Anthology

A Cultural Revival: Four Seasons Hotel Jakarta

New York-based interior designer Alexandra Champalimaud brings her detail-oriented and culture-inspired design vision to the Four Seasons brand in Jakarta. Olha Romaniuk writes.

An expert in residential and hospitality interiors, Alexandra Champalimaud has a keen eye for design enriched by a deep understanding of local history and a sense of place. Having established her New York-based firm, Champalimaud, over 30 years ago, Alexandra has been tirelessly expanding her extensive design portfolio with a roster of renowned commissions such as the award-winning Algonquin Hotel in New York and the Waldorf Astoria. Despite and because of her international experiences, Champalimaud remains profoundly attune to the unique conditions of every project, executing designs that exhibit a keen understanding of their surroundings. With her latest hospitality project, the Four Seasons Jakarta, Champalimaud discusses her firm’s comprehensive design process for the hotel.

How do you approach each of your projects? Is there a systematic brainstorming process that you follow before you begin design or is the approach to every project different?

Every project requires a different thought process, depending on what the requests of the client are. There are numerous factors we take into account before starting each project, such as respect for local cultures and traditions. With the Jakarta project, we had the opportunity to tell the story of its past, present and future through our design and, therefore, naturally had to do our research. We take into account history, heritage and cultural context all while keeping longevity and timelessness in mind.

Four Seasons has been a staple on Jakarta’s hospitality scene for over 20 years. With the new building and new location, was there any intent to redefine or update the Four Seasons brand through interior design as well?

We were directed to create a magnificent space that could appeal to the guests and the locals on several levels. The hotel had to be designed to fit into its urban, sophisticated space, while remaining true to the Four Seasons brand, which is known for its absolutely world-class luxury hospitality experience.

Your studio is known for unique designs that tell a story and have their own character and personality. What message and personality do you hope the new Four Seasons Hotel Jakarta will convey to visitors?

We wanted to convey the local culture, history and traditions of both Asian and European cultures – Jakarta’s local traditions and its history with Western Europe, and the Dutch who traveled to the city as spice traders and left their mark on the region. The Dutch influences are conveyed, for example, in the design of Nautilus bar, which features a large mural of schooners en route to port with delicately swirling lines in the carpet to evoke the feel of the ocean.

For Four Seasons Jakarta, we wanted guests to be enveloped by the spirit of the space at the first moment of their arrival, which we did by creating an entrance of amazing scale, enormous height and elegance – [and a space that is also] contemporary, fresh and young.

Aside from being influenced by Indonesia’s Dutch Colonial period, what other cultural influences did you incorporate into the design?

We [made reference to] Indonesian design such as the gilded, hand-carved tiles affixed to the ceiling of The Library, which is a private space with handsome seating and jewel-toned walls. Meanwhile, Indonesians love their chocolate but adore jewellery even more, so we designed a patisserie to house an array of sweets in the fashion of a jewel box with gilded geometric trim. One of my favourite details are the his and hers custom-designed chairs found in the sitting area of the private suites.

The lobby and the main staircase are particularly spectacular. What are some of the design details within these spaces that were designed to create a big impact as visitors entered the hotel?

There are many – the classical, gilded, 8.5-metre-high open space with ornamental metal work entry door and divider screens, the marble staircase with a custom vibrant rug, an almost 5-metre-high water feature carved in stone, the custom relief artwork from Hadiprana, the crystal chandelier from Lasvit…

In comparison with the hotel’s public spaces, the rooms appear more understated.

The guest rooms are a play on international culture coming to Jakarta, such as the Dutch in the 17th century, but also a reflection of the time when Jakarta was first founded. The rooms are classical in scale with a hint of modern details – a mix of late 18th, 19th and early 20th century furnishings. We chose a grey-blue colour scheme because it is one of the most sophisticated gentle colours, and is both uplifting and calming.

Were there any particular design challenges that you encountered during the design process?

One of the challenges we faced was how to convey this exciting city with its rich history and constant movement, where the women are fabulous and chic, and there is a delightful blend of different cultures. When I first visited Jakarta, I felt an undeniable pull towards the city and its people and when we were, then, approached with this project opportunity, we had the chance to tell the story of the city’s past, present and future through our design.

Marie Christine Dorner: Furniture Design from an Architectural Perspective for Habitus Living

Interior and furniture designer Marie Christine Dorner discusses spatial sensibilities, balancing design influences and her creative partnership with Ligne Roset. Olha Romaniuk writes.

http://www.habitusliving.com.sg/community/marie-christine-dorner-furniture-design-from-an-architectural-perspective

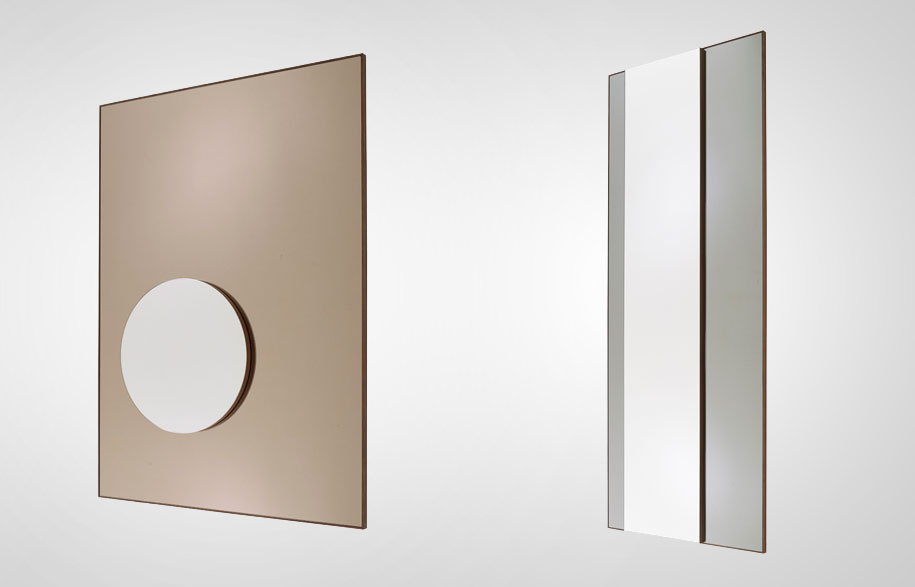

With an unmistakable architectonic quality present in her interior and furniture designs, Marie Christine Dorner is a master at combining functional and poetic elements in her multifaceted projects. In her latest project for French furniture company Ligne Roset, Dorner’s keen sense of architectural space, along with her affinity for storytelling and material exploration, shines through, resulting in objects that appeal to the cognitive and physical experience of spatiality at once. Selected pieces from her 2015 and 2016 collections were exhibited at this year’s International Furniture Fair Singapore.

For Dorner, who studied at the École Camondo in Paris where she now lectures, furniture and interior design go hand-in-hand. The designer attributes this perception to Camondo’s teaching approach that integrates interior and furniture design within one curriculum. A constant element throughout her projects, Dorner’s sensitivity to architectural space and the way a human body relates to it translate into insightful visual and physical design solutions in her interior projects and furniture pieces.

“Every time I design a piece of furniture, I feel like I am designing architecture on a smaller scale,” says Dorner. “For me a piece of furniture is a space. It should be seen in its context. And whenever I design a space, I feel that it is a collage of furniture. Of course, with a piece of furniture you are closer to the body than in a space, but a space is close to the body as well. It all has to be designed in a very human scale.”

Dorner, who has lived in metropolitan cities like London, Paris and Tokyo has acquired an intuitive way of balancing her Eastern and Western influences. She realised her penchant for experimenting with different materials during the early phases of her career. For her defining 2004 show, Une Forme/ One Shape, Dorner explored a chosen shape in different materials, based on the notion that design must be seen as an art where the material comes first. The concept was put into production by Ligne Roset some years later with the ONE SHAPE sofa and table produced in white ceramic, black-stained oak and natural oak finishes.

According to Dorner, her long-standing professional relationship with Ligne Roset commenced about 10 years ago, when Michel Roset took note of the designer’s CRASH low table prototype – photos of which Dorner had sent to Ligne Roset two years prior.

In 2015 and 2016, Dorner completed two consistent collections of furniture for Ligne Roset. For both collections, Dorner experimented with various aspects of storytelling and materiality to create collections that represented a small universe and drew inspiration from architectural elements.

“I was trying to use materials to create a small universe, like a small town in a reduced scale,” elaborates Dorner. “ALLITÉRATION, the book shelf, is a good example of this. It attempts to present a bookshelf as a small building in a context of a space – how a bookshelf can emphasise emptiness and presence and give rhythm to a space.”

These days, Dorner is busier than ever. She is working on an upcoming collection for Ligne Roset, as well as projects ranging from private residences to a collaboration with a kitchen brand. Despite the various project typologies and scales, Dorner’s passion for storytelling and material exploration remains a consistent thread in her work.

Dorner has also expressed interest in working with textiles and redesigning hotels. “I always want to tell a story when I design something,” concludes Dorner. “If you buy a piece of furniture, it has to answer your questions. Similarly, with hotel design, it is a very nice typology for a designer, because it gives a great opportunity to tell a story, to create a full universe and make people dream.”

10 Questions with... Silvio d'Ascia for Interior Design Magazine

http://www.interiordesign.net/slideshows/detail/8952-10-questions-with-silvio-dascia/15/

Even before opening his architectural agency in 2001, Silvio d’Ascia has had a particular interest in transit hubs as unique building typologies. Having completed his Ph.D. about new urbanity for the city of the next millennium in the mid-90’s, d’Ascia has continued his research and experimentation in this specialized typology by taking on projects that explore transportation hubs as urban linkages between the public and the surrounding context of the cities. D’Ascia’s practice today continues to focus on projects—transit hubs and high-speed rail stations, cultural and housing developments—that connect to their surrounding context and the public. With a number of such projects in the works for Silvio d’Ascia Architecture and an upcoming book on rail stations of the future, d’Ascia discusses the importance of well-designed public spaces and his research in the area of transportation architecture.

Interior Design: What is the overarching philosophy of your firm? How does this philosophy influence your approach to your projects?

Silvio d'Ascia: Each project begins with an ambition to explore, what I call, a Neo-humanist dimension of architecture. The architect—a sort of “enlightened” individual in the Renaissance sense of the term—has the task of translating modern society’s needs, desires, dreams in a profound and meaningful way for our cities, regions and countries, all the while taking into consideration socioeconomic and cultural contexts. In so doing, one seeks a contemporary urban form: spaces that generate (once again) shared common spaces that encourage social wellbeing, sharing and communication.

Architecture, in general, must create a link between space and society, even more so today, as our everyday practices become increasingly immaterial and abstract (smartphones, nanotechnologies, artificial intelligence, etc.).

ID: What is unique to your work process that distinguishes your studio from others?

SA: What sets the agency apart is its commitment to design that fosters communal living—design that attempts to devise new ways of living together in original spaces, or in spaces that use cultural imprints (heritage projects, cultural institutions—both physical and psychological) in unexpected ways. The agency is becoming more and more aggressive in its analysis and research of an architecture embodying the ideals of shared spaces, even if we find ourselves today confronted with a paradoxically individualist mindset.

Perhaps the easiest building typology we work with that exemplifies such research would be the train station or transit hub. This is such a rich area of exploration for the agency, as it allows us to tackle a wide array of issues related to living and movement, interaction and solitude.

ID: Has your studio changed or evolved since it started?

SA: Fortunately, yes! It would be silly to say that we are not evolving or learning from our previous experiences. What is important, however, is that we continue to move in a direction that takes advantage of the opportunities and the lessons learned from all experiences, both the successes and the projects that did not quite make it off the ground.

I started working in 1993. More than twenty years later, it is obvious that a lot has changed, not only in my personal sphere of influence but also in the architectural profession as a whole. One should attempt to give Architecture (with a capital “A”) an identity that reflects these changes, outside of what one could term as passing (or passé) trends.

ID: Silvia d’Ascia architecture has a long track record in working on transit hubs. What initiated your interest in this particular typology?

SA: The transit hub typology, for us, represents a singular opportunity to investigate and question what a “new” urban form could and should be. It was with the arrival of the high-speed (TGV) train in France in the early 90’s that really deepened my understanding and fascination with this project type. For me, one could say that the invention of the TGV changed our society in a profound way: all of a sudden, we were confronted with a new set of values, different needs and new possibilities to dream. Our realm of opportunities became larger—people could more easily commute to and from work and this is to say nothing of the prospects of a newfound mobility for leisure travel. Mountains, seaside, rural villages, other metropolises—they all became more accessible.

While the invention of the high-speed train was something ingenious, the train and the train station remained elements very-much known to the public. How to, then, fit this new contraption within a societal context already understood? What’s more, with the arrival of high-speed trains came a resurgence in the rail station as a true urban hub—a nexus for international, national, regional, and local rail travel, and a hub for metro and light rail systems, bus lines, taxi stands, cars, motorcycles, bikes. The station had to confront and resolve all of these moving parts.

The fact that a vast majority of these stations are of a classical architectural style all the more emphasized the need to understand and propose contemporary solutions to mobility and user comfort. It is a situation unique to Europe, for sure, with all of the classical station structures located throughout the continent. They serve, in their various forms, as sort of monuments or temples to transport. For me, working within this typology means respecting this history in transcribing it in an updated architectural language.

The agency has had the opportunity to work on over twenty major rail station projects. The major references include the Porta Susa high-speed station in Turin, Italy, a high-speed station in Besançon, France, the Montesanto regional station in Naples, Italy and the new high-speed station for Kenitra, Morocco, currently under construction.

ID: What is your approach to this very specialised typology? What things do you consider when designing a transit hub?

SA: I consider a rail station to be a plug-in or a connecting element linking city and outlying regions. It is, at once, a transit hub and a place wherein one finds an array of services dedicated to urban life. The most successful examples of this building type go above and beyond the simple programming of these spaces. Instead, they generate exciting and unique public spaces. It is why a rail station is vastly different from an airport, which has its own set of criteria and service spaces and is an element disconnected from the cityspace. Sometimes rail stations are this way as well and that is a shame.

Our approach, then, is about generating a station as a public space: a porous, communicative, and evolving environment. The agency strives to reveal the “double nature” of a station as a place serving as a landmark for the city and as an element that facilitates travel. This ebb and flow, the coming and going, the idea of “staying” or “leaving” allows us to create stations that embody the intriguing threshold that exists within their walls.

ID: With your expertise in transportation hub projects, what do you think the rail station of the future should be like and what conditions does it need to respond to?

SA: In short, the train station of the future is revolutionary in its insistence on serving as a unifying element for the city and its suburbs. In so doing, the station begins to tackle the multitude of questions related to socioeconomic well-being, diversity, equality. The station as a public institution—but also as a living entity—is unique. As the building should also adapt and re-adapt the programs found within its core, the station of the tomorrow is a surprisingly organizational element, and could be the one project typology capable of giving a true vision of the contemporary society—its problems, yes, but also its potential.

ID: What is the difference, if any, between working with clients in Europe versus clients in Asia?

SA: The differences between Europe and Asia appear (at least on a superficial level) to not be to the advantage of European architects. Whereas in Asia, projects advance at a rapid pace, here in Europe and specifically in France, we are confronted with administrative procedures and decision-making processes often times confounding and sometimes disastrous.

A similarity, though, could be that we both remain ambitious. There are differences in scale but there is still the intention and desire to challenge, impress and build. It is not all for the best, of course, but when something exceptional occurs on the architectural scene, both arenas seem to take note. However, I will say that my personal experience has been that, here in Europe, ambition has been reduced to an individual level. It has become privatized, with this privatization sometimes using political structures to further its motives. Globalization, though, has made such conversation necessary.

ID: Your firm participates in a lot of international competitions. What is the appeal of the process of competitions to you?

SA: The sheer challenge makes open competitions quite exciting. Jokingly, maybe I am calling on a sort of subconscious thirst for arena combat, thanks to my Italian roots.

Confronting other architects, other ways of conceiving space is truly a source of inspiration. Sure, it is exhausting and one must separate expectations from reality but, at their best, architectural competitions give our agency a wonderful opportunity to evolve.

ID: What kind of projects do you seek out when you choose to enter competitions?

SA: Well, it comes as no surprise that we do our best to find transit hub competitions or projects related to rail infrastructure. We also go after projects in sectors related to innovation and heritage. With innovation, I am talking about data centers, incubators and the like. This, again, is an area the agency has had a fair amount of success in, with two built technology campuses in Shanghai. The heritage project typology relates to projects where there is a need to renovate, transform or restructure an existing building, potentially adding to it a new structure, as well. Our project for the Maeght Foundation in Southern France exhibits this typology with a renovation of the existing building and gardens designed by Sert, a disciple of Le Corbusier and an addition to the museum buildings.

Cultural projects, thereby, provide a natural environment within which the agency can explore heritage and memory. However, we also encounter these topics in many of our housing projects, as a vast majority of them involve what we call a surélévation, whereby you create a rooftop addition to an existing building. We have three of these projects currently under development in Paris, so this provides an exciting occasion to construct on the rooftops of Paris—a landscape unto itself.

ID: What projects are in the works for you now?

SA: This year will be critical for us in that we have a number of projects under construction. We have two housing projects nearing completion in Paris. There is also a technology center for the RATP (Parisian transit authority) just on the outskirts of the city. Plus, we have an office building complex under construction in Nancy, France. Finally, there is our high-speed station in Kenitra, Morocco, which is an ongoing project. Outside of these construction sites, we have a hotel project in Paris that is in its early design phase. There is also a handful of research projects that we are continuing—one of which is focusing on the rail station of the future. We hope to release it as a book later this year.